Although people are living longer, it seems companies are not doing so well. The Boston Consultancy Group reported that the life span of corporations nearly halved over just three decades. And research from Yale shows that the average lifespan of an S&P 500 company has decreased from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years in 2012.

We’ve all seen companies disappear in our lifetimes – remember Woolworths and Blockbuster video? Kodak?

Several authors have observed that it is often a company’s success that sets it up for failure. Managers rely too heavily on doing the same thing that made the company successful in the first place. The success is then used as evidence that they should continue with the same strategy.

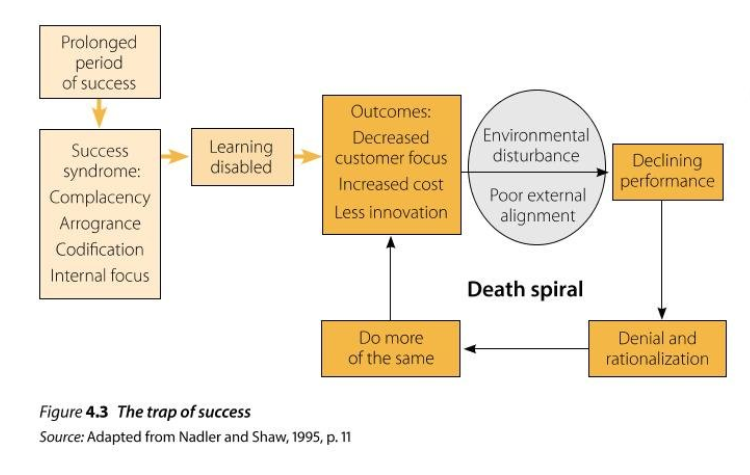

Nadler and Shaw (1995, cited in Hayes (2014)) observed that this complacency can be the company’s downfall. As the company grows and becomes more complex, the focus switches away from the external environment and instead to internal issues. This leads to declining performance in the market. But managers think the solution is to do more of the thing which has led to success in the past. As the environment has changed, this doesn’t have the success they expect. Nadler and Shaw describe the organisation as becoming ‘learning disabled’.

Unless the company changes, it can go into the ‘death spiral’:

So it is incredibly important to be aware of what’s happening in the environment and to be willing to adapt and innovate for a successful future.

It’s not just companies. We can think of this happening at the individual level too. For example, we get promoted but keep working in the same way we did before. We don’t adapt to the role and learn the new skills required. We double down, working harder and harder with the same strategy that made us successful before. Eventually, if we don’t learn and adapt, we fail. In the words of Marshall Goldsmith’s book – what got you here won’t get you there.

Past success doesn’t necessarily mean future success. We all need to continuously learn, adapt and grow.

References

Hayes (2014) The Theory and Practice of Change Management, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 4th ed.