In the previous post I explained that, in order to conserve energy, the brain turns things we do repeatedly into habits, so we can do the actions without having to think.

It’s worth pausing here and learning a bit more about habits, as so much individual and organisational change involves us changing our behaviour and habits in some way.

Researchers have shown that 40-45% of the decisions we make every day are actually habits – we don’t make a conscious decision at all. And anyone who’s tried to start a new positive habit (like exercising, healthy eating or meditating) or change an existing habit, will know just how easily we can slip back into our usual way of doing things.

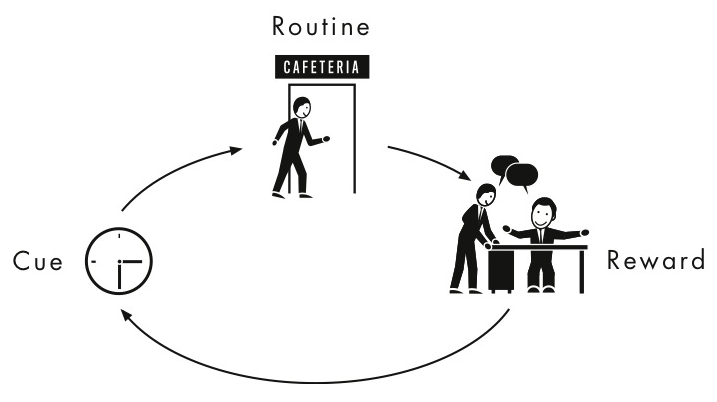

Charles Duhigg in his book The Power of Habit explains how researchers have identified the habit process as a 3-step loop:

- A cue, that tells the brain to go into automatic mode, and which habit to use

- The routine – which can be physical, mental or emotional

- A reward – which helps the brain decide if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.

In this example, the cue could be ‘arriving at work’, the routine is you ‘go to the cafeteria to get a coffee’, and the reward is you get to chat to your colleagues in the cafe before you start the working day. (In the brain, the actual reward is the dopamine that is released.)

Over time, and with repetition, the loop becomes more and more automatic. And over time, the brain begins to anticipate the reward, releasing dopamine at the thought of it, and therefore there is a craving for the reward, which keeps the habit going.

Change requires people to concentrate until they have adapted to new cues and routines, and this takes energy. So knowing about habit loops can help us change our habits or develop new ones.

More on this in the next post…

References

Duhigg, C (2013) The Power of Habit: Why we do what we do and how to change, London: Random House