In the last post I talked about change load and change fatigue when there’s just too much change in a short period of time. Following on from this, it’s clear that change is experienced at the individual level – a small change might mean a minor adjustment for you but might be overwhelming for someone else.

Britt Andreatta in her book ‘Wired to Resist’ takes up this point. I love her ideas as she has developed some visual tools to help you really think about the effect of changes on you and your team/organisation. You can listen to her explaining some of her ideas in this 10-minute video:

To start, she states that the effect of the change on any individual depends on four factors:

- The time it takes for that person to get used to the change

- The amount of disruption it causes them

- The total number of changes they’re managing

- How fast the changes are coming

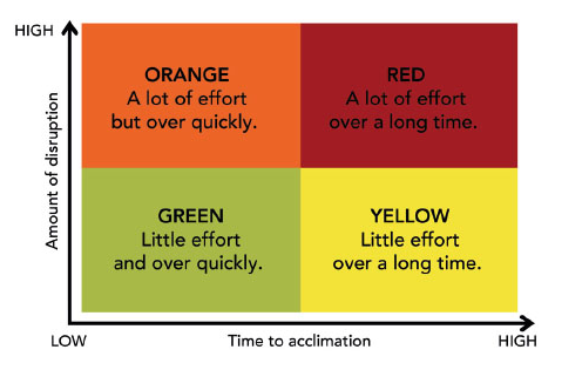

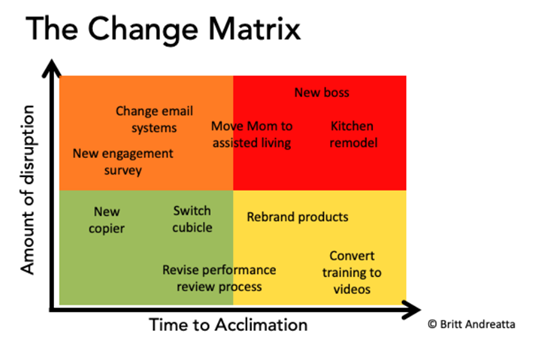

Bringing the first two factors together gives you the ‘change matrix’.

So if the disruption the change causes is small, and the time it takes to get used to the change is small (‘time to acclimation’), then you can consider this to be ‘green’ – the effect will probably be small.

But if disruption is high and it takes a lot of time to get used to the change, the change can be classed as ‘red’.

Individuals can then place whatever change is planned on this matrix.

But as Andreatta outlines, there are other factors in play here. You’re going to react differently depending on whether you chose the change and if you want the change.

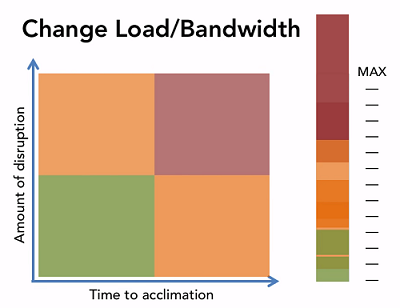

And we also have to consider our earlier idea of change load. When changes come together and start overlapping, their effect changes. Two ‘orange’ changes may become a darker orange, and eventually a red. If you stack lots of changes on top of each other, you may meet or exceed your limits.

And we need to remember as individuals that organisational change overlaps with life changes. If your employee is going through a big life change at the moment, organisational changes are going to have a bigger effect (and vice versa).

Planning with the effects of change in mind

The book goes on to outline a new model to help managers plan changes in their organisation. But for now, what I love about this is that it shows managers in the organisation that they have some tools and some control, indeed some responsibility, for managing changes so their staff aren’t overloaded.

In recent years, we have seen high and increasing stress levels at work and the response has often seemed to push the responsibility onto the individual employee – resilience training, yoga classes, meditation classes, and so on. But companies can be more aware of all the changes across their organisation and track them. Is someone noticing the fact that a massive IT rollout is happening at the same time as an office move and restructuring for one particular department? Is an individual manager noticing that a team member is moving house at the same time as her role changes?

Organisations are made up of people. As humans we can adapt, but we also have to work within the limitations of the technology we’re built with – our brains. I’ll talk more about the brain in the next few posts.

References:

Andreatta, B. (2017), Wired to Resist: The Brain Science of Why Change Fails and a New Model for Driving Success

If you’re interested in learning more about the ideas in Britt Andreatta’s book, she is currently offering the ‘Change Quest model’ online course for free until June 30th 2020.