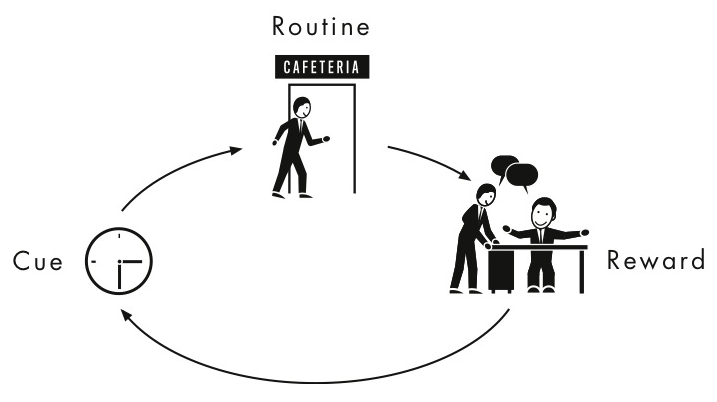

In the previous post I explained how the brain develops ‘habit loops’ to conserve energy. A habit loop consists of 3 steps: a cue, the routine, and a reward. Being aware of what is triggering your habits and routines is the first step to making a change.

A habit develops when you repeat the same choices. So in order to change the habit we need to make different choices until a new or different habit is formed.

In the example below, every morning after you arrive at work you go to the cafeteria first, buy a coffee and take it back to your desk. But this is getting expensive, and you’re trying to cut down on caffeine. You want to change the habit, but it’s automatic.

Cues

If you want to change a habit, you need to identify the cue. What is triggering this behaviour? Research suggests that there are five possible categories for the cue, which are:

- Location – where are you when the urge hits? What can you see?

- Time – does it happen at a regular time?

- Emotional State – does it happen when you are tired? Angry? Sad?

- Other People – who else is around?

- Immediately preceding action – do you always do this after something else?

So in the current example, you can see several possible cues. You always go to the cafeteria for a coffee:

- at work (location)

- when you arrive (immediately preceding action), which is usually

- at 8.30am (time)

So if you want to change your habit, you need to look at these more closely. Do you go for a coffee if you don’t arrive till later in the day? What happens at the weekend or if you work from home? Is it time or location?

Reward

It’s also worth experimenting with the reward. What is the actual reward you’re getting? What happens if you still go to the café but buy a green tea instead? Or what if you bring in a flask of coffee, avoid the café and go direct to your desk. Are you trying to avoid starting work? Do you want to chat to colleagues in the café before you start? Is it the taste of the coffee? Or something else?

Once you better understand the cue and reward, try keeping the cue, but changing the routine or reward.

Have a look at this video to see how Charles Duhigg changed his afternoon cookie habit.

Starting a new habit.

You can also use the idea of cues and rewards to create a new, good habit.

Set the cue and reward and make a plan. For example:

- At 9am (cue)

- I will put on my trainers and go for a 20-minute run (routine).

- When I get back I’ll have a piece of chocolate (reward).

And actually, you only need the chocolate reward while you’re developing the habit. After lots of repetitions, the chocolate reward will no longer be needed. The routine is reward itself.

Your turn

Give it a try. Think of one thing you’d like to change, or a new habit you’d like to start. Let me know how you get on!

Further Reading

How Habits Work – excerpt from the book ‘The Power of Habit’ by Charles Duhigg