As humans we are constantly adapting to our environment. But it’s clear from what I’ve said about the brain that changing just one person (ourselves) can be scary and difficult. So what about if an entire team, organisation or society needs to change? That means every single person in that group needs to shift.

There’s a vast array of literature on ‘change management’ and a whole industry built on it. We’re regularly told that between 50 and 75% of organisational change initiatives fail. The cost of making changes and the cost of failure can be immense. No wonder, then, that companies spend a vast amount of money on change management consultancy (around $10 billion a year according to the Boston Consultancy Group).

So what’s going on? Why do we have to keep ‘changing’ and how do you decide what needs to change, if anything?

Change is inevitable

Like it or not, our environment is changing all the time. Managers talk about leading in a VUCA world – one that’s Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous – and there’s debate about whether the pace of change is increasing, but it certainly feels that way. We’ve all seen big changes in our lifetime.

Changes in Technology

Just think about how we listen to music. I grew up with vinyl records, then tapes and Walkmans and Ghetto blasters, then CDs and portable CDs, then mini-disks, now MP3 players, and now it’s on my mobile phone or tablet with wireless headphones. Social media didn’t exist 20 years ago and now it’s ubiquitous. How did we manage without it? The rate of technological change seems to be increasing and every time there’s a change, we have to adapt and learn something new.

Changes in Society

We’re living longer. Improvements in medicine and living conditions mean that half of babies born now will live to be over 100.

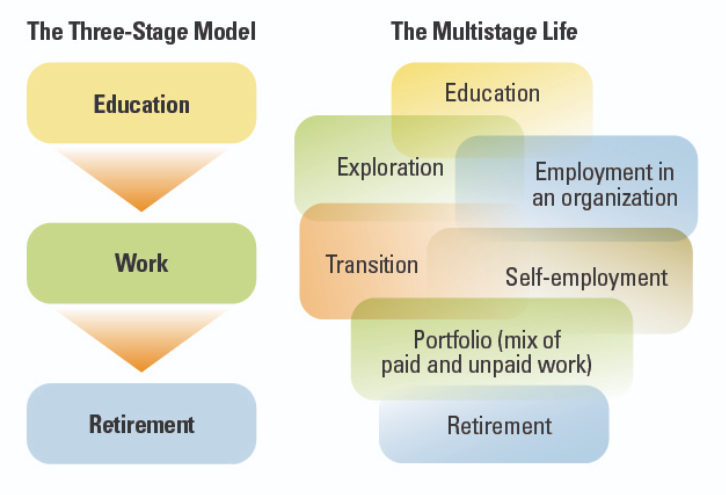

But many companies and governments are still working on a 3-stage life model. We get educated when we’re young, we work for 45 years, then we retire. But that’s unsustainable if we’re all living longer. We can’t afford to retire at 65 if we’re going to live to 100, and we will need to re-skill and shift careers more often. This is causing tension.

And the makeup of the workforce has changed. There are more women in work and dual-income couples with children. For many the Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 model doesn’t work well. Employees are demanding more flexibility, and a more educated workforce want more meaning in their work lives.

All this has a big influence on how we live and work. Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott identify we are now shifting into a multi-stage life. This means more change, more transitions, more breaks, education across the lifespan and more flexibility:

Changes in Work

Whole industries are being disrupted as new competitors emerge. Just think about Uber disrupting the taxi industry, or AirBnB disrupting the hotel industry. And AI is threatening to remove jobs currently done by humans. This has knock-on effects with people being pushed out of jobs and having to retrain.

Technological changes allow many of us to work from anywhere, anytime. The rise of the gig economy has brought flexibility and autonomy for many but also financial insecurity.

Even in a ‘stable’ career like medicine there is constant change, with a need for re-education and learning as new techniques and medicines appear.

Managing and Leading Change

So the need for change is clear as we have to adapt to the inevitable changes going on in our environment. The human brain is designed for survival – to avoid threats and seek rewards. And organisations and societies, too, need to constantly adapt in order to survive and thrive.

Managing or leading change in organisations has huge implications for the individuals working in those organisations. Over the next few posts I’ll introduce some tools and models used in managing planned change. But we should always remember that at a basic level, organisations and teams are made up of individual human beings and knowing how individual humans work will make all the difference.

References

Gratton, L. and Scott, A. (2016) The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity, London: Bloomsbury